For the 160th anniversary of First Bull Run, I offer a not wholly facetious counterfactual, explaining how two Pennsylvania Militia officers, perhaps mere lieutenants, could have shortened the Civil War by nearly four years.

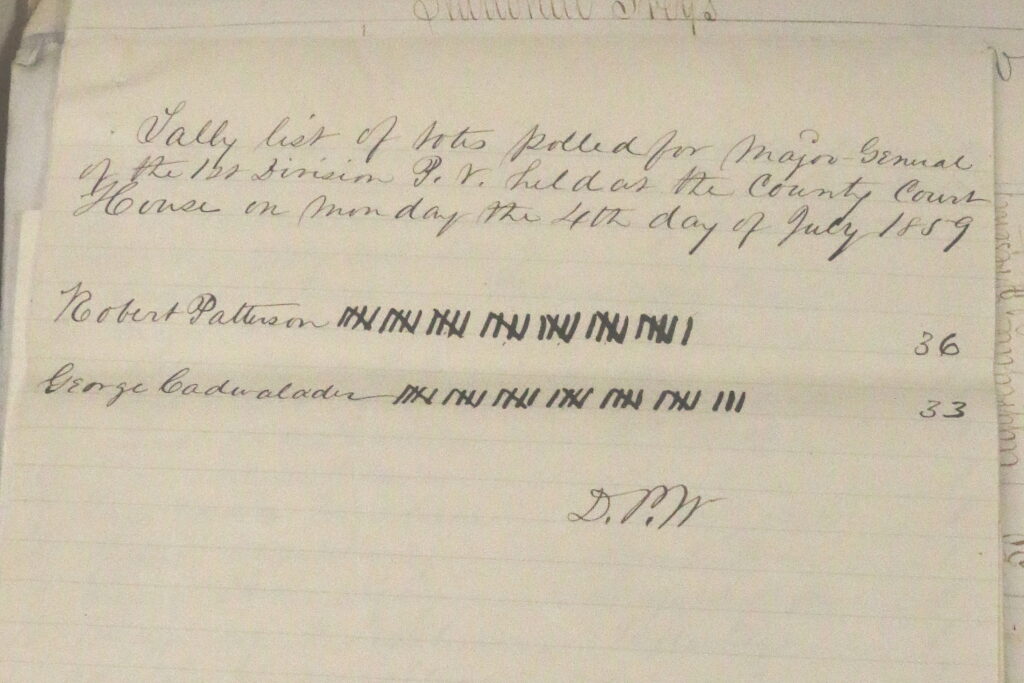

The story begins on July 4, 1859, when the officers of the First Division, Pennsylvania Militia, gather to elect a major general. In our timeline, they vote 36-33 to re-elect Robert Patterson, who has commanded the division since 1833.

A fine soldier in his youth, Patterson is by now “a tired and indecisive old man,” in the words of historian Ethan Rafuse. As a Democrat and owner of Louisiana plantations, Patterson may have southern sympathies as well.

Here’s the counterfactual: two officers switch their votes. By a margin of 35-34, the new division commander is George Cadwalader.

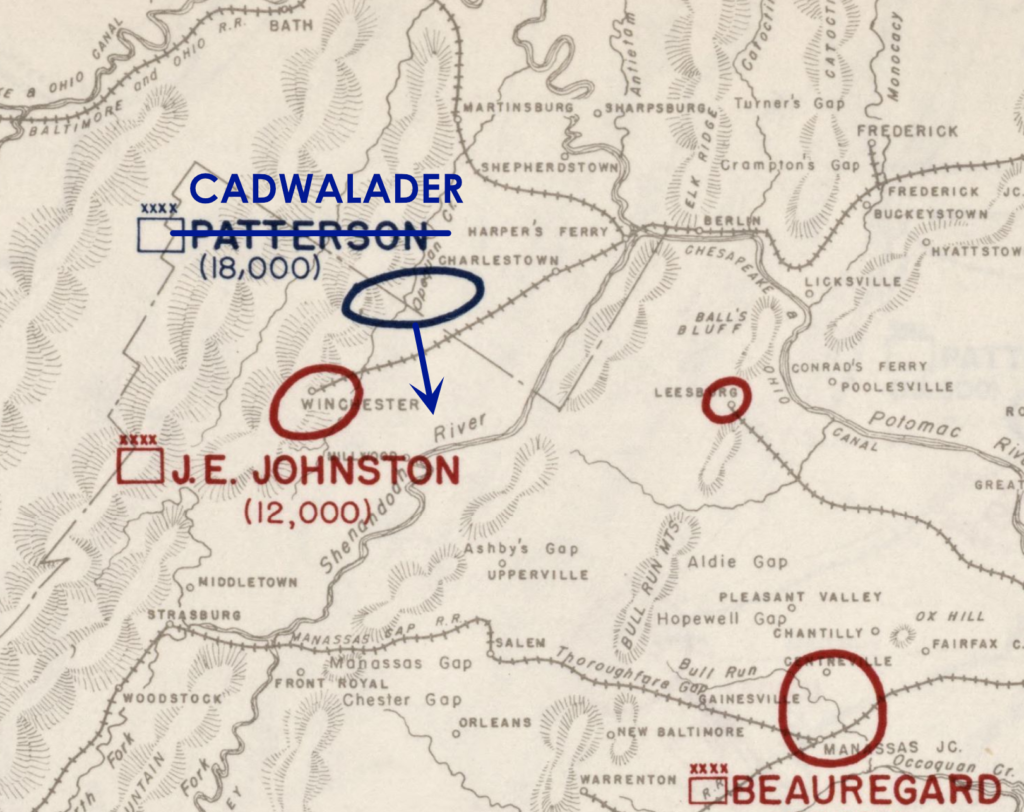

As a result (and I have not explored just how likely this is), two summers later, in July 1861, it is Cadwalader, not Patterson, who commands the 18,000-man Army of Pennsylvania in the northern Shenandoah Valley.

It is Cadwalader, not Patterson, who receives Winfield Scott’s order to beat, or at least detain, Joseph Johnston’s Confederate forces in Winchester.

And while he knows that the Pennsylvanians with him in Virginia are essentially civilians whose enlistments are about to expire, he’s led citizen soldiers against rebels before, back in Southwark.

And Cadwalader has a plan: “If we had moved upon Berryville and got upon [Johnston’s] right flank, and he could not have moved one foot without our being upon his flank, we could have been at Manassas sooner than he could and could have attacked him at any moment.”

Imagine, then, Cadwalader in command of the Army of Pennsylvania. He swears, and maybe he drinks. He moves on Berryville, between Johnston’s army and the Shenandoah River, stopping Johnston from joining Beauregard or at least delaying him until after McDowell’s attack.

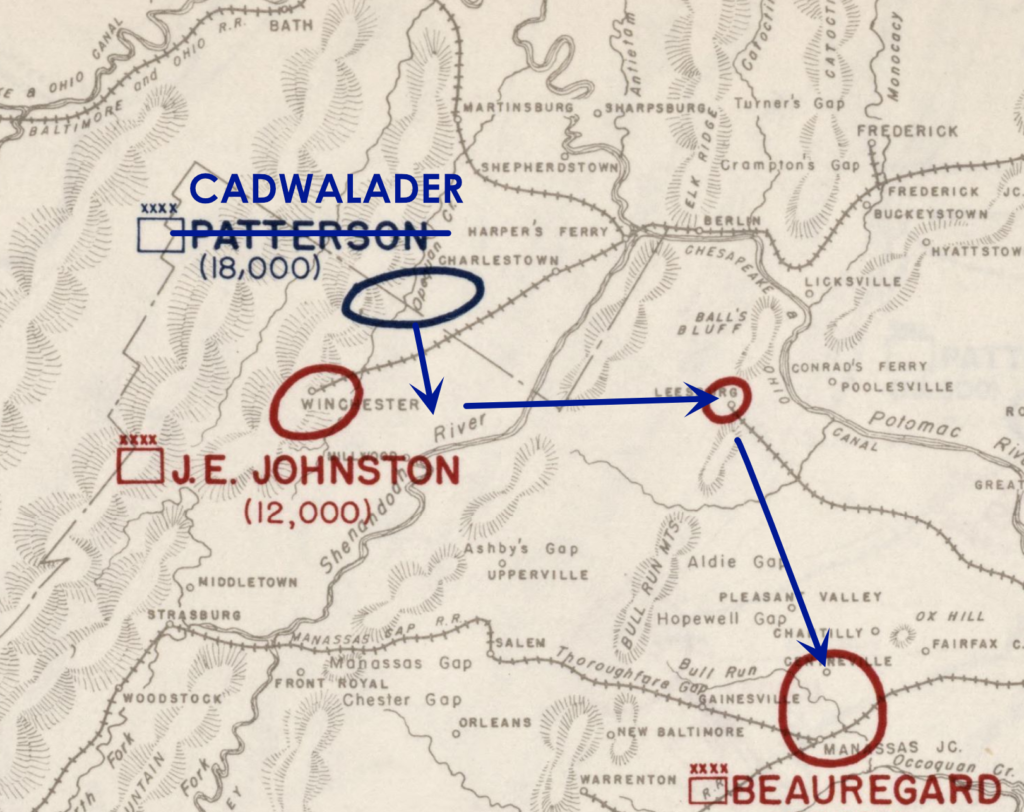

Alternatively, as Cadwalader suggests in his 1862 testimony, he marches to Manassas via Leesburg, and thus reinforces McDowell at the same time that Johnston reinforces Beauregard.

Either way, the preponderance of Union strength prevails at Bull Run.

The Confederate forces retreat to Richmond, pursued by a superior Union force. By the end of July 1861, Richmond is back under U.S. control, and victory is near. All thanks to two militia officers who voted for Cadwalader, subduer of rebels.